Safety net

The different layers of the safety net have been added to a model, illustrated as circles around the patient. The service providers are arranged in layers, depending on how close they are to the patient. The family will therefore be situated closest to the patient in the model, followed by the services, and in the outermost layers we will find the layers that govern the services, such as legislation, instructions and supervision.

The report highlights various issues at municipal and central government level that could constitute a risk of children and adolescents not being identified and receiving the necessary healthcare. Furthermore, the report describes various aspects associated with the layers in the safety net and how the situational awareness of the various service providers can influence the overall support. We will begin by looking at Jonas and his family’s first encounter with the support system.

Jonas

An adolescent who needs support

We will never know how Jonas felt and how he experienced the support system. His parents’ narrative can provide us with a glimpse into what Jonas might have experienced and what he and his family were offered in terms of support. Jonas expressed that he would rather not stand out. He wanted to become an engineer.

The problems he had keeping up at school meant that both the school and the educational and psychological counselling service became involved. His difficulties at school were assessed several times. Jonas had a total of five caseworkers from the educational and psychological counselling service. He was diagnosed with dyslexia during upper secondary school.

Jonas had one appointment with the municipal psychologist and five or six chats with a youth worker. The school nurse was also brought in, as Jonas was inattentive and seemed to be very tired. The school nurse found that it was difficult to arrange meetings with Jonas. The school notified the Child Welfare Service when Jonas was in the tenth year of school due to high levels of absence.

In upper secondary school, Jonas contacted his GP to have his absence from school certified. He gradually dropped out of school. In an interview, his mother said:

"He had major academic shortfalls when he started upper secondary school as a result of the high level of absence during lower secondary school. Yet we still found that our boy was proud to be starting, that he was looking forward to and motivated by going to upper secondary school. The start of the first school year went well. But, as time went on, there was work to hand in and there were tests to sit. This became difficult for him and, without a diagnosis, he did not receive any extra support. We had hoped that there would be someone who would see him and provide him with the follow-up he needed."

Jonas encountered many professionals and underwent numerous assessments during his school years. The problems simply grew. The last thing that was tried was a referral to CAP, but CAP found that Jonas was not entitled to healthcare from the specialist health service.

Even for specialists, it can be difficult to differentiate the symptoms of serious illness from more normal issues that are common during the teenage years, on the basis of an assessment. The refusal from CAP was based on an assessment of the referral alone and the specialist health service had no direct dialogue with Jonas, his parents or his GP.

It can be difficult to give a complete overview of symptoms in children and adolescents who are being assessed for mental health problems. Jonas went to see his GP with somatic complaints. It was difficult for both his parents and the GP to get an understanding of what really bothered him. The GP became concerned that the complaints could be symptomatic of mental illness. Adolescents may find it difficult to identify and convey mental health issues and symptoms using words. The ability to describe your own ailments and concerns improves with age.

It can also be extremely difficult for adolescents to accept support or to show others that they need support. Even adolescents experiencing significant challenges may appear uninterested in receiving support and many may resist conversation-based treatment. It can seem unusual or frightening to put emotions into words. In adolescents, resistance to engaging with a treatment relationship can easily be interpreted as a lack of motivation or a lack of desire to receive healthcare and perhaps also a sign that the condition is not serious. This makes it especially challenging to assess and treat adolescents.

The Children’s Ombudsman’s report “Jeg skulle hatt BUP i en koffert” (4) (“If only I had CAP in my pocket”) concludes that the services currently are not able to adapt support to individual children’s life situation and needs to an adequate extent. This is clearly illustrated in Jonas’ story. The support was not adapted for him and his parents say that they wished there was someone who could see what he needed. Trust and a positive relationship are prerequisites and support must be available when it suits the adolescent.

There is professional agreement that early intervention is important (5). Specialist health services for children and adolescents are, in principle, organised in the same way as the services for adults, with referrals, assessments, deadlines, waiting times and admissions. Local governments have established separate mental health services for adults, while mental health services for children are managed by many different service providers. The support and organisation of the services are not always sufficiently adapted for the reality of adolescents. Jonas did not like all the meetings and the way things were organised with assessments, meetings and many different service providers was something he found difficult.

Waiting time guarantees for treatment within the specialist health service

The specialist health service has a waiting time guarantee.

Waiting times can be difficult to cope with for adolescents who have experienced difficulties over an extended period of time. Professor of Sociology Kari Dyregrov writes that we lose the opportunity to support many adolescents because the health service has not been adapted for their needs (6).

From a patient safety perspective, waiting time may, in itself, represent a risk of children and adolescents who need healthcare not being identified.

We lack knowledge of how Jonas felt about the two refused referrals to CAP and how he felt about the fact that no agency took responsibility for further follow-up. We have no basis on which to link his suicide to the refusals. What we can assume is that vulnerable adolescents may experience refusals for support as a rejection. The feeling of being rejected may exacerbate the symptomatic pressure associated with mental illness. We have heard, both from service users and health service employees, that refusals for healthcare can be painful.

It is a patient safety risk when children and adolescents are passed between service providers. Both the services available and the responsibilities are unclear. A service in which various forms of referrals are sent by one service provider to another with the adolescent as a communicator will increase the burden on the adolescent. A refusal from the specialist health service itself can, in such a context, also be viewed as a patient safety risk.

A referral from a GP to CAP is often the result of a lengthy process and extensive dialogue with the adolescent themselves, their family and often also other municipal support agencies. An important basis for the referral is the adolescent’s own motivation to accept support. Adolescents who experience difficulties may experience varying motivation over time. Adolescents’ experiences of the support system may influence their confidence that there is support available. It can be difficult to stay motivated.

The family

"We tried to get him off to school every single morning."

Jonas’ parents were distraught when he did not receive the support they felt he needed at school and they felt that he had to deal with too many different agencies.

"In summary, there have been a great deal of meetings, but no measures aimed at our son’s learning situation"

Worried about her son

Jonas’ mother mentioned to his GP that she was worried about him and that she felt that he was not getting the support he needed. They agreed to make a referral to CAP.

Jonas’ parents were unprepared for and disappointed by the refusals. They thought he would get help from CAP.

"It cannot be asking that much to invite someone in for a meeting."

His parents experienced a boy who struggled with schoolwork. Jonas mastered activities in many other areas, he was social and had a lot of contact with friends. His parents wanted him to get support with what he was struggling with at school. And a progress plan for how to work with it.

Parents are the closest layer in a safety net surrounding an adolescent who experiences difficulties. They know the adolescent and are able to observe changes and nuances that others cannot see. Jonas’ parents played the part of mediators of their son’s needs, both with school and the GP, who acts as a gatekeeper to mental healthcare for children and adolescents. Even though parents play an important role as protectors, this is often not enough. The other layers of the safety net have to cooperate in order to ensure that the adolescent receives support.

The School

The role of the school

Children and adolescents spend a great deal of time at school and school forms an important part of the safety net intended to identify pupils who are experiencing difficulties.

In primary school, Jonas already struggled to put letters together and mixed his words up when reading. We know that he was tested during primary school, but we have not yet looked more closely at the measures that were implemented. The school contacted the educational and psychological counselling service in consultation with Jonas’ parents. In the referral to the educational and psychological counselling service, it was stated that the school did not have enough teaching or assistant resources to meet Jonas’ needs. Jonas will participate with the resources that are already in the class, in smaller groups and with more follow-up when there are more adults in the class.

School problems escalates

Despite the fact that the educational and psychological counselling service became involved, the issues at school escalated over the years. His parents found that Jonas was increasingly lagging behind. Eventually, he stopped going to school and ended up with a high level of absence. The school also sent a message of concern to the Child Welfare Service concerning the high levels of absence from school. The school also contacted the school nurse. It looks as though the objective of the interventions from the support agencies was to get Jonas back to school.

HIB’s mandate is limited to investigating serious events and other serious matters within the health and social care services. We do not have a mandate to address the school’s follow-up of Jonas.

Many people tried, but no-one succeeded in uncovering the severity of the symptoms Jonas struggled with. His parents told us that “the warning lights came on early” and that they felt that he did not get enough support at school.

Children with learning disabilities

Assessments and inspection reports that we have looked at as part of the investigation indicate that the municipalities do not always ensure that systematic interaction is facilitated when it comes to children and adolescents who experience difficulties. There is a high risk that children who experience difficulties with learning will develop health problems over time.

Jonas was not admitted to the upper secondary school he had put down as his first choice, neither was he admitted to his second choice, despite having applied on special grounds. Specialisation in general studies was his third choice and he managed to get a place here with the assistance of the school management at lower secondary school.

It poses a risk to children and adolescents when the municipal services, including schools, are unable to provide adequate and comprehensive support.

Jonas’ mother explained that he was called in for a meeting with a counsellor and his class teacher before Christmas during his second year of upper secondary school due to absences. He was told at the meeting that he had no chance of completing his education. He went to the meeting alone and was extremely upset afterwards. Jonas was completely alone when he received this brutal message. His parents wish that they had been able to be there with Jonas during that meeting.

A major reason for dropping out in upper secondary school is inadequate literacy skills (8). Figures from Statistics Norway show that 78.1 per cent of pupils and apprentices complete their upper secondary education in five or six years (9). There seems to be a correlation between having difficulties with learning, absence from school and mental health, but there has been relatively little research into this (10).

The educational and psychological counselling service

Among other things, the educational and psychological counselling service will help schools make arrangements for pupils with special needs and prepare specialist assessments when needed (7).

Jonas’ mother was unhappy that time in school was spent on assessments and reports without anything being implemented in the classroom. The first educational and psychological counselling service assessment was not completed before Jonas was 12 years old. This showed unsatisfactory reading development, but that there was no basis for a diagnosis of dyslexia. The educational and psychological counselling service proposed various measures for the school to follow up on. HIB has not looked at whether the measures were followed up on (i).

The educational and psychological counselling service was involved in several instances, including together with other municipal agencies. There was a constant change of caseworkers during Jonas’ school years. In total, he had five caseworkers from the educational and psychological counselling service.

Jonas was diagnosed with dyslexia

The educational and psychological counselling service conducted two specialist assessments of Jonas, the last while Jonas was at upper secondary school. This time, Jonas was diagnosed with dyslexia and his upper secondary school was supposed to facilitate his learning on this basis. The educational and psychological counselling service did not have any contact with Jonas or the school after the last assessment.

It is very important for a dyslexia diagnosis to be made early on during the school pathway, so that school-related challenges can be followed up with measures early enough to ensure that the pupil does not fall behind. Since it falls outside of the mandate of HIB, we have not investigated the potential reasons why the educational and psychological counselling service only diagnosed Jonas with dyslexia when he was attending upper secondary school. Nevertheless, we are able to establish that the educational and psychological counselling service, as a safety net, was not sufficient for Jonas to keep up at school.

Objectives and measures

Ever since primary school, Jonas found that he struggled to master school work without sufficient facilitation or measures being put into place. When the diagnosis was made when he was in upper secondary school, Jonas had fallen so far behind that he was largely unable to follow the teaching. Inadequate mastery at school may predispose vulnerable adolescents to the development of mental illness (12).

It represents a risk to children and adolescents when educational and psychological counselling service assessments are not followed up with specific objectives and measures.

The GP

GPs play an important part in the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents and are responsible for making referrals for specialist support when needed. The GP has an important role in the safety net surrounding adolescents who are experiencing difficulties.

The GP is part of the municipal health service, as established in Section 3-2(13) of the Norwegian Healthcare Act.

Jonas’ GP was familiar with both Jonas and his family. While in upper secondary school, Jonas frequently went to his GP to get medical certificates for his absences. The GP eventually became concerned about Jonas, without being able to ascertain exactly what it was the boy was struggling with.

The GP has a central role

In the event of mild mental health issues, the GP, often together with the school nurse and other municipal resources, will play a central role in a supportive treatment team. Even though the GP did not receive any information about Jonas, either from the educational and psychological counselling service or the school nurse, he learned from Jonas’ mother that these support agencies had been involved.

There are several instances in legislation that set out provisions concerning cooperation at system level, for example in Section 2-1(3) of the regulations on health centres and the school health service (15). This provision stipulates that health centres and the school health service shall have procedures in place for cooperation with e.g. GPs.

Additionally, Section 8 of the General Practitioner Regulations contains a provision that imposes a responsibility on the municipalities to facilitate cooperation between GPs and other service providers and to ensure appropriate and effective integration of the general practitioner service within the municipality’s other health and social care services.

It represents a risk to children and adolescents when GPs are not integrated in the municipality’s other health and social care services.

The GP as gatekeeper

The GP is the professional who decides whether a patient requires treatment via the specialist health service and who will make a referral for assessment and any treatment in the special health service when healthcare provided by the GP and the municipality is not sufficient.

The GP sent a referral to CAP when he was unable to determine the cause of Jonas’ complaints. He felt that there was a need for diagnostic assessment.

It represents a risk to children and adolescents when CAP refuses a referral from a GP without the adolescent having been ensured further healthcare.

The GP’s gatekeeper role was overruled twice by the specialist health service. Jonas did not receive any healthcare after this.

The school nurse

The school nurse is crucial to health-related promotion and prevention. This is a key function in the work of identifying and following up on adolescents who experience psychosocial challenges.

The school nurse at lower secondary school was contacted because of increasing levels of absence from school. The school nurse was one of several agencies tasked with talking to Jonas to encourage him to go to school. It can be difficult for the school health service to reach adolescents, especially boys. Adolescents may experience conversational follow-up to be tiring and useless. A successful outcome requires getting into a position that results in trust being established. In order for conversations to be used as protective measures, there must be adequate efforts made on the part of the resource. It can take time to establish a relationship characterised by trust.

Jonas rarely attended school on the days when the school nurse was there. She had little contact with other services on shared objectives and measures. The continuity of the contact was broken by her absence and the service was somewhat detached from both family and other municipal service providers. The limited availability meant that the intervention had limited benefit. The school nurse

It represents a risk to children and adolescents

- when a school nurse follows up on adolescents without specific objectives having been established for the intervention

- when insufficient interaction procedures have been established

- when it is unclear who will follow up in the event that the school nurse is absent and when the adolescent changes schools

In 2018, the Children’s Ombudsman conducted a survey of the provisions of the school health service, which found that only 40 per cent of respondents have a nurse at school that they can visit as needed (16). There is a serious lack of school nurses, which means that this service is poorly equipped to perform the statutory work of following up on pupils.

It represents a risk to children and adolescents when a school nurse has too little capacity.

The government recently held a consultation on an amendment to the regulations on health centres and the school health service. The proposal concerns the service also being able to provide the necessary treatment and follow-up for milder mental health issues and somatic conditions. Even if the proposal is passed, this could be a challenging task for a service that is already under-resourced. The treatment of mental illness, even when mild, requires specialist expertise accrued through specialist training and continuous experience-based supervision in a treatment environment.

It represents a risk to children and adolescents when the school nurse service is expected to be a low-threshold service and it is under-resourced.

Another patient safety risk will arise if an already marginal health promotion service is also assigned responsibility to provide treatment.

The government is committed to strengthening the municipal health services for children and adolescents and has highlighted the school nurse service as an important service provider. The school nurse service already appears under-resourced and vulnerable, with major challenges linked to capacity, availability and continuity.

The Family's House

The municipalities have various services for identifying and supporting adolescents. Jonas lived in a municipality that had the Family's House. The Family's House is tasked with safeguarding the mental and physical health of pregnant women, children and adolescents (17). The Family's House is an initiative for health-related promotion and prevention that the Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services recommends that municipalities have.

When Jonas was in the tenth year of school, concerns about him increasingly grew both at home and at school due to the high levels of absence from school. A multidisciplinary team from the Family's House was introduced. In this case, the team consisted of a municipal psychologist and a youth worker

The youth worker was tasked with getting Jonas to go to school and to be someone Jonas could talk to. The youth worker met with Jonas several times and felt that she managed to develop some sort of rapport with him. This work ended when Jonas started upper secondary school, as the youth worker worked with lower secondary schools.

The Family's House is an initiative intended to promote multidisciplinarity and cooperation. The service is organised and managed in various ways in different municipalities and often cooperates with other agencies, such as GPs, other municipal services and CAP. The “Psykisk helsearbeid for barn og unge i kommunene” (“Mental health interventions for children and adolescents in the municipalities”) instructions emphasise the model as a suitable low-threshold service that can ensure quick and comprehensive support for children and adolescents (18).

Jonas’ GP was not informed of the support provided by the Family's House and CAP was also not aware of how the Family's House had been involved.

It represents a risk to children and adolescents when different multidisciplinary services in the municipality fail to interact regarding objectives and measures and when it is unclear whether anyone has a coordinating responsibility. The risk increases when individual services are not aware of one another’s involvement and there is no exchange of necessary information.

The Child Welfare Service

The Child Welfare Service shall ensure that children and adolescents who live in conditions that may be harmful to their health and development receive the necessary support, care and protection at the right time (19). The Child Welfare Service is therefore part of the safety net.

Large school absence led to a message of concern

In Jonas’ case, it was the frequent and undocumented absence from school that resulted in school, during the tenth year of school, sending a message of concern to the Child Welfare Service. The Child Welfare Service also did not proceed to assess potential causes of the high levels of absence from school. According to his parents, the involvement of the Child Welfare Service caused an additional burden for Jonas. The Child Welfare Service has an independent right to make referrals to CAP. This right was not exercised in the case of Jonas.

The specialist health service – CAP

CAP is a specialist health service within the mental healthcare system for children and adolescents and provides assessment, diagnosis and treatment of mental health symptoms and conditions. The main duties of CAP are to support children and adolescents between the ages of 0 and 18 and their families with assessments, treatment, advice and facilitation. CAP therefore has an important role to play in the safety net intended to identify and provide the correct support for adolescents suffering from mental illness.

CAP is a second-line service that will provide healthcare that cannot be provided through the municipal health services, including the GP service. An adolescent who experiences difficulties and is assessed by CAP will often have gone through a lengthy municipal process before contact is made with CAP.

CAP refusals

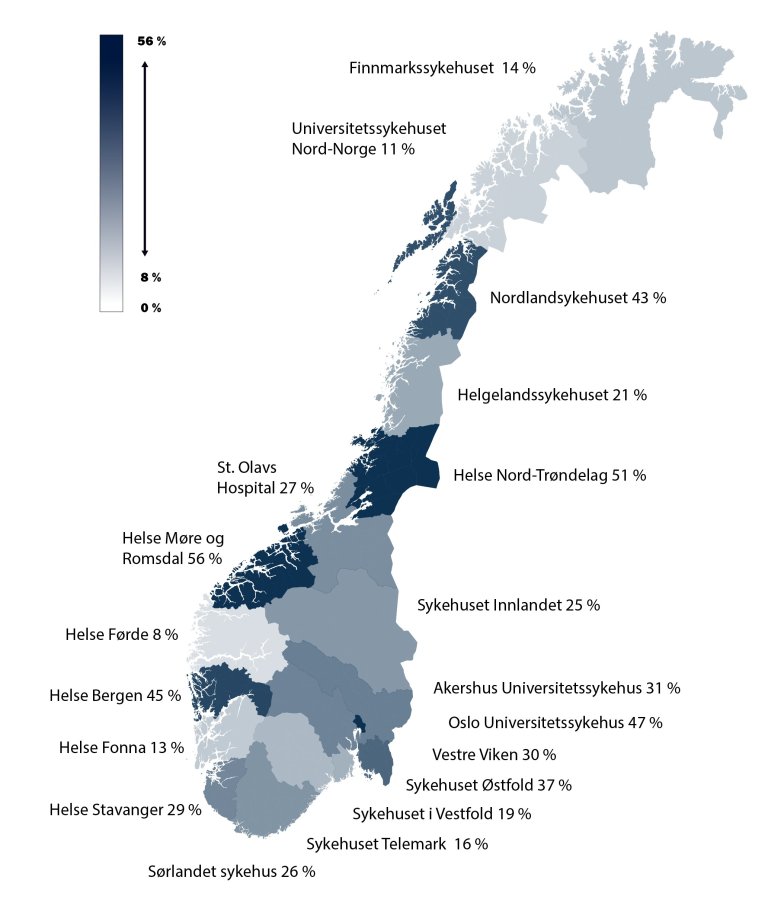

There is great variation between the health trusts with regard to the proportion of referrals that are eligible for healthcare from CAP. Some of this variation may be an expression of a combination of professional variation and elements of different registration practices. In 2019, the number of new referrals that were refused varied between 8 and 56 per cent at health trust level. It could represent a risk to patient safety that there is such great variation in the refusal rates.

How many children and adolescents receive support from CAP?

Activity data from the health service can provide us with insight into the scope of healthcare provided within each discipline. We have looked at figures from the Norwegian Patient Register that show, among other things, the number of new referrals to and the number of refusals from CAP. These figures have only been collated and used to a limited extent previously and there could therefore be some uncertainty surrounding the quality of the figures. All refused referrals are reported back from the Norwegian Patient Register to the reporting units each months and broken down to patient level, so that the extent can be checked. Nevertheless, the proportion of refusal is still high enough that we must note that there could be differences in the registration practices that we have not been able to determine the cause of.

Many of the services aimed at children and adolescents are provided by the municipal health services, but there are currently no underlying figures that can provide a useful, comprehensive overview of these services. We do not know whether a high refusal percentage in a health trust is compensated through a corresponding increase in municipal services within the catchment area.

The figures from the Norwegian Patient Register show that, in 2019, 26,469 new referrals were made to the mental healthcare system for children and adolescents and more than 56,000 children and adolescents received treatment (20). The number of children and adolescents who received treatment corresponds to 5 per cent of the population under the age of 18. Nevertheless, there are variations within the regions and between regions and the proportion varies from 4 per cent in Vestre Viken and Oslo to 7 per cent in the Førde area and Helgeland.

Variations in CAP, which is a service within the mental healthcare system for children and adolescents, is not necessarily a reflection of the overall quality of the service. However, geographical variation in the use of healthcare services could be an expression of a quality issue if there are no professional explanations for the variations.

National trends in the specialist health services – CAP

The Norwegian Directorate of Health presents analyses of and governing data for the trends and variations in the specialist health service. The latest report on services in the mental healthcare system was published in September 2020 (21). Most CAP patients receive outpatient treatment.

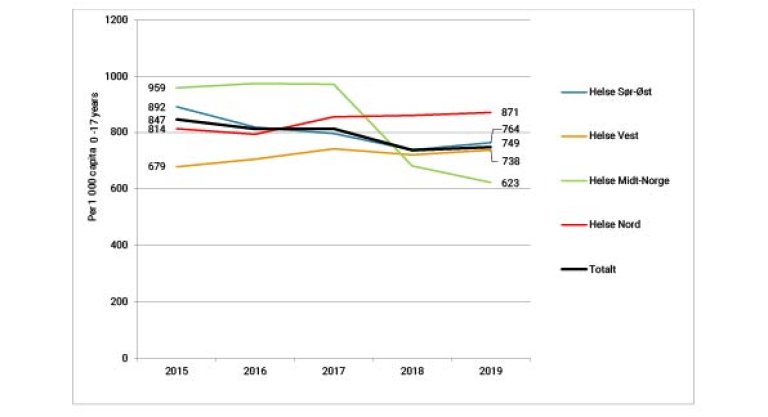

During the last 20 years, there has been growth in the number of patients treated in mental healthcare system for children and adolescents. As a result of the national escalation plan for mental health for the 1998-2008 (3) period, the proportion of the child and adolescent population that was in contact with the service increased from around 2 to nearly 5 per cent. This growth was primarily the result of outpatient activities. These activities levelled off after the escalation period. The number of outpatient contacts decreased from 2015 to 2019.

If we take a closer look at the trends in regional health trusts, it confirms that there have not been more outpatient contacts per capita in recent years. Registered outpatient contacts decreased by 12 per cent from 2015 to 2019:

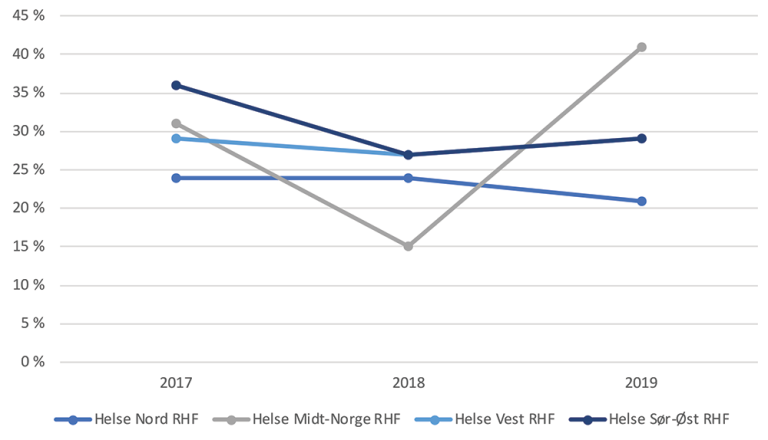

CAP refusals – major differences in Norway

The figures show that there are variations between the health regions, including within a relatively short period of time. These could be real variations, but could also be due to challenges relating to data quality.

The Central Norway Regional Health Trust has the greatest variation from year to year. The trend in activity in the Central Norway Regional Health Trust is partly linked to a change in reporting system. We have limited knowledge of the real trend.

In general, the refusal figures are consistently high from year to year. Refusals vary between health trusts, from 8 to 56 per cent, as shown in the map of Norway below. We must note that the variation is likely to be not only an expression of professional variation, but that there are also elements of different registration practices.

Whether the differences in refusal percentage are due to different referral practices is not something we have been able to look at. Nevertheless, the differences in refusal rates are so great that it would be difficult to explain these variations through differing referral rates.

Differences in refusals between somatic healthcare services and CAP

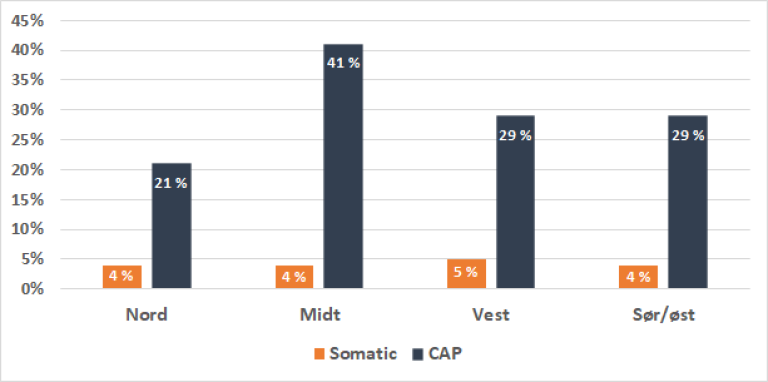

For the country as a whole in 2019, an average of 29 per cent of referrals to CAP were refused.

Compared to figures from the somatic healthcare services for children (0-17 years of age), the CAP refusal rate is high. The Norwegian Patient Register figures for refusal in somatic healthcare are evenly distributed across the health regions for 2019, with between 3 and 7 per cent refused. Figures from CAP for the same period show that the proportion who were refused varied between 21 and 41 per cent between the different health regions.

A large proportion of those who are referred to CAP receive a refusal. It is extremely rare that children and adolescents are refused in somatic healthcare.

The large variation in the CAP refusal percentage indicates that referrals are not assessed in the same way across the country and this represents a risk of children and adolescents not receiving the necessary healthcare.

The variation is not only evident from geographical differences. We can also see that there is not equal availability in the specialist health service across disciplines. The figures show that it is much harder for adolescents to be entitled to healthcare from CAP than to receive somatic healthcare from the specialist health service.

Patient pathway refusals

There are also great variations between the regions when it comes to the patient pathway for mental health and substance abuse. In the report “Pakkeforløp psykisk helse og rus” (“Patient pathway for mental health and substance abuse”) (22), the Norwegian Directorate of Health shows that 19 per cent of those who were referred for a patient pathway within mental health for children and adolescents during the first four months of 2020 were found not to be entitled to healthcare in the specialist health service. There is variation between the regions – from 7 percent in the Northern Norway Regional Health Trust to 26 per cent in Central Norway Regional Health Trust.

Referrals

Referrals to the specialist health service are the primary health service’s tool for communicating a need for a specialist assessment so that a patient can progress with treatment.

The first assessment of such a referral is largely based on the written content of the referral and therefore also the level of precision used in the specification of the patient’s symptoms. It can be difficult to identify symptoms that carry an entitlement to healthcare in children and adolescents who struggle with mental health issues. It can be challenging for the referrer to write a referral that captures everything. Often, an undiagnosed mental health issue can be precisely the reason why a patient is referred. When the specialist health service assesses the referral, emphasis will be placed on prognostic signs, i.e. factors that may provide an indication of the condition and the need for healthcare. The specialists will then use the priority instructions for mental healthcare for children and adolescents in the assessment (23).

Specialist assessment of undeclared condition

The GP referred Jonas to CAP because he felt an assessment of an undiagnosed mental health issue was necessary. Children and adolescents do not always manage to put their complaints into words and it can therefore be difficult for a GP to write a comprehensive referral. Nevertheless, a patient should not lose their entitlement to healthcare even if a referral is inadequate.

The referrer may supplement the referral by obtaining additional information from other municipal services. CAP occasionally receives co-referrals that are attached to the GP’s referral. Co-referrals can be written by e.g. the school nurse or the educational and psychological counselling service to help ensure that CAP has a better overview of the patient’s challenges and what has already been undertaken within the municipal health service.

A separate form template has also been prepared and can be used for the referral of children and adolescents for mental healthcare within the specialist health service. The form can be downloaded and completed electronically. We have not assessed the use of this form.

Interaction regarding referrals

Various tools and procedures have been developed to ensure that patients receive the necessary healthcare.

There are clear expectations for those who make referrals to the specialist health service. Nevertheless, the specialist health service cannot refuse a referral on the basis of inadequate information. Among other things, the instructions state: “The requirement for professionally sound practices may indicate that the person assessing the referral should contact the patient or referrer for additional information.”

The instructions use words such as “could” and “should”, but also state that the referrals “must” still be assessed. The specialist health service can only refuse a referral if there is no need for healthcare through the specialist health service. In the event of uncertainty as to whether the patient is entitled to healthcare, a good solution would be to invite the patient in for an assessment. The most important thing is to avoid refusing patients who should be entitled to healthcare.

When Jonas was referred to CAP, no local interaction procedures had been established with regard to referrals. Electronic message exchange had not been introduced locally at the time that the referral was assessed. Such message exchange can simplify interaction. The GP states that he has rarely received any questions about referrals he has made. The referrals are either refused or the patient is admitted.

The GP: "I might have had one phone call. My reality and theirs differ. They are a team while I am on my own making the assessment. I am not always certain that it is a case of mental illness."

The specialist psychologist at CAP states that he would now most likely have used electronic message exchange with the GP to obtain additional information. If CAP had been more aware of the measures that had already been attempted, this would likely have influenced the assessment.

In the CAP refusal letter, it was stated that the referral did not include information about any measures that might have been implemented in the municipality. CAP also did not request such information.

Different understanding of needs

Patients, GPs and specialists in district psychiatric centres have a different understanding of the premises for when a patient should receive healthcare from a district psychiatric centre (26). The Office of the Auditor General of Norway has found that two out of three GPs believe that GPs and hospital doctors have a different understanding of when there is a need for specialist health services within the mental healthcare system (27). Equally many hospital doctors working in mental health believe the same.

In 2020, on commission from the Department of Health and Social Care, the Norwegian Directorate of Health described potential forms of collaboration between municipal services and the specialist health service. This was part of the preparations for the work to implement better procedures to clarify support requirements for children and adolescents. A key premise of this work was the fact that children and adolescents must receive the right support at the right time and in the right place. The smallest possible number should experience refusals and proper information about the services must be provided. The outcomes of the work have yet to be published.

In the recently published report “Jeg skulle hatt BUP i en koffert” (4) (“If only I had CAP in my pocket”), the Children’s Ombudsman also notes the need to clarify the allocation of responsibilities between the municipalities and the specialist health service. According to the Children’s Ombudsman, there is a need for clearer guidelines as to which mental health support services should be available at a municipal level.

Prioritisation and the priority instructions in CAP

The priority instructions (23) are intended as a practical tool for use in assessing whether a patient who has been referred is entitled to healthcare from the specialist health service. The instructions will contribute to equality in the assessment of entitlement regardless of where in the country you live. Anyone who assesses referrals must have a common understanding of the regulations that govern patient rights. The priority instructions are detailed in the specification of who is entitled to treatment and what is required to receive support from CAP. It is intended as a tool for ensuring proper patient treatment and correct use of resources.

Not severe enough

Those involved in supporting Jonas in his home municipality struggled to understand what was bothering him. The referral shows that there were concerns about depression. In the referral, the GP also requested neuropsychological testing to “determine any functional challenges once and for all”. CAP only assessed parts of the GP’s referral against the priority instructions before a refusal was issued. Even though the GP described being unable to determine what was bothering Jonas but that he saw a clear functional decline, CAP found that he was not entitled to an assessment by the specialist health service.

Both refusals were justified by the difficulties described not being severe enough to carry an entitlement to healthcare from the specialist health service. In its justification, CAP emphasised only one of the symptoms mentioned in the referral, namely the absence from school. According to the priority instructions, absence from school or school refusal alone does not entitle the patient to healthcare.

The way the instructions were applied here, the instructions contributed to narrowing Jonas’ ability to receive support, as the presence of one symptom had been assigned exclusionary weighting. The significant functional decline on the part of Jonas was not identified.

The priority instructions also did not contribute to CAP performing a different or separate assessment of Jonas after the GP sent referral number two.

It represents a patient safety risk when the priority instructions are applied in such a way that individual information contained in a referral is weighted more importantly than the overall concerns on the part of the referrer. It also represents an additional risk when a second referral is not identified as a signal of increased concern.

It represents a patient safety risk when the priority instructions do not place particular emphasis on the fact that undiagnosed mental health issues may entitle the patient concerned to healthcare.

HIB finds that the priority instructions are largely based around symptoms of diagnoses and that it is more adapted to the specialist health service than the needs of the patient and the primary health service.

Principles of prioritisation

In the prioritisation report (28) from the Ministry of Health and Social Care, the Norwegian parliament endorsed measures in the health service being assessed based on three priority criteria: the usefulness criterion, the resource criterion and the severity criterion. In other words, when the specialist health service assesses the need for healthcare, it must use these three criteria as the basis:

The usefulness criterion: The priority of a measure increases if the usefulness of the measure is great. The usefulness of a measure is assessed based on whether knowledge-based practice indicates that healthcare can increase the patient’s life span and/or quality of life.

The resource criterion: The priority of a measure increases if the measure does not take up excessive resources.

The severity criterion: The priority of a measure increases if the measure will be used to treat a serious condition. The current situation, duration and loss of future years of life all have an impact on how the degree of severity is assessed.

The criteria must be assessed collectively. The use of more resources will be accepted if a condition is serious and the treatment has good effect. The prioritisation regulations and the priority instructions must reflect these criteria.

CAP did not consider Jonas’ condition to be serious enough to entitle him to healthcare. The other criteria, the usefulness and resource criteria, were not highlighted in the assessment itself. A decent life span is used as a measure of the usefulness or health benefits of a measure. It is difficult to quantify the effect of measures in mental healthcare for children and adolescents. By identifying and meeting needs at an early stage, it is possible to avoid conditions becoming worse. Such a preventive perspective makes priority assessments complex, particularly in individual assessments.

The application of the principle of the lowest effective level of care is often based on the fact that the specialist health services are more resource-intensive than municipal health services. As many patients as possible should receive support in the municipality, as healthcare is then provided closer to the patient. This is considered to be a cost-effective approach from both a patient and a resource perspective. Nevertheless, it does not always have to be the case that the municipality is the lowest effective level of care, especially not if the municipality has already initiated measures and does not have any further capacity or sufficient expertise to move forward.

The resource investment must be assessed based on a comprehensive view of the health service and not solely on the basis of the cost burden a measure inflicts on the undertaking in question.

The health trust found that Jonas should receive support in the municipality. The priority instructions have been designed in such a way that resource use in this context is mainly assessed from a specialist health service perspective. Resource use in the municipality is not taken into account when the specialist health service assesses a referral.

It represents a patient safety risk if the specialist health service refuses healthcare and refers the patient for follow-up in the municipality without knowing whether the municipality has the capacity and expertise to provide such follow-up.

The significance of the ten-day deadline for the assessment of referrals

The specialist health service, including CAP, has, in line with the Norwegian act on patient and user rights (29), a deadline of ten days to assess whether a patient is entitled to the necessary healthcare. In this work, the service is aided by the prioritisation regulations (30) and the priority instructions (23).

The specialist psychologist who assessed the referral has said, among other things:

“One of the challenges associated with admissions is knowing whether you have enough information or whether you require further information to reach a conclusion. There could be a real risk that you have to hurry in order not to exceed the ten-day deadline. There may be cases in which the GP has been unable to fully highlight the child’s challenges and it turns out that there is a lot more than what has been presented.”

The health trusts are measured on whether they respond within the ten-day deadline. The ten-day deadline is a quality indicator and a parameter that is monitored by the health trust boards. The indicator is reported on to the health authorities (31). This deadline is largely met by CAPs in Norway (98.4 per cent). The deadline compliance rate has been above 93.8 per cent since 2011.

In 2013 and 2014, the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision conducted a nationwide audit of outpatient clinics for child and adolescent psychiatry (32). The audit addressed, among other things, the acceptance and assessment of referrals. One of the findings was that the majority of referrals were assessed within ten working days, but failures were identified in connection with the management of inadequate referrals.

Governing objectives on compliance with deadlines may influence how referrals are assessed.

The ten-day deadline as a quality indicator and the need to comply with the deadline may result in CAP not taking sufficient time to obtain supplementary information from the referrer. This may represent a risk to patient safety, especially when it is also not ensured that children and adolescents are followed up by the primary health service in the event of refusals.

Patient rights

The right to healthcare is a key element in the safety net designed to identify children and adolescents who need support. HIB has looked at the conditions in the current legislation that contribute to increasing the risk of healthcare not being provided.

The duty to ensure necessary and reliable health and social care services

The duties incumbent upon the government, including regional health trusts and municipalities, must facilitate people receiving necessary and reliable healthcare.

The government’s duty to provide entails requirements relating to legislation, organisation and financial allocation. The government must have an overview of the health and social care services and ensure that the necessary capacity and services are available. Furthermore, it must also facilitate those working in the health and social care services being able to fulfil their duties, including the duty to provide reliable healthcare. In the current regulations, this responsibility has been assigned to the specialist health service and the municipal health and social care services.

In the Norwegian Health Personnel Act (35), the legislation also assigns responsibility to health personnel to provide patients with the necessary information, reliable healthcare and emergency assistance.

The right to necessary and reliable healthcare

Children and adolescents have a statutory right to immediate, necessary and reliable healthcare. This right is reflected in the aforementioned duties.

Healthcare being necessary also involves a requirement to investigate a condition. The requirement of reliability not only sets out requirements concerning the professional quality and scope of treatment but also the quality of the assessment of referrals to ensure that the service is provided on time.

The form of healthcare that is considered appropriate in a specific situation must be based on the contents of legal and medical standards. The legal standard is expressed through multiple legal provisions and in practice. The duty to interact, refer and examine patients is stipulated in several legal provisions. The duty to facilitate means that CAP must ensure that the assessment of referrals is conducted in a reliable manner.

It is a basic principle for both levels of the health and social care services to act responsibly and refer patients on if this is considered necessary for the patient to receive necessary and reliable support.

The organisation of the health services is based on the principle that support should be provided at the lowest level of care possible and as close to the patient as possible. There is significant variation between the different municipal services. The line between what is considered the responsibility of the specialist health service and what should be managed by the municipalities is not always clear and may vary depending on local resources and traditions.

In Jonas’ case, the GP had assessed his condition over time and believed that support from the specialist health service was necessary. CAP refused the referral and referred him to the municipal services without performing any further assessment of what the municipality had done and the extent to which the municipal agencies could contribute further follow-up.

The fact that we have two different sets of regulations that overlap with regard to patient rights means that grey areas may occur. Jonas needed help, but the service levels had a different understanding of whose responsibility it was to provide such help.

There is a risk to patient safety when the allocation of responsibilities between the municipal health service and the specialist health service is unclear.

There is a risk to patient safety when the right to necessary healthcare in the specialist health service is refused without the content of and responsibility for continued healthcare in the municipality having been clarified.

Interaction

“In summary, there have been a great deal of meetings, but no measures aimed at our son’s learning situation. Those who have been involved no doubt did the best they could with the resources available to them.” - his father.

According to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (37), all children have a right to proper healthcare and support must be adapted for children. Adults must do what is best for children. The services must then adjust to actually ask what children and adolescents need. This requires the services intended to support children not only to demonstrate effective interaction, but that they also have a common understanding – about needs and what constitutes proper support – that the adolescent can agree with.

Many agencies were engaged to support Jonas during his school years. He was referred through a system that it is difficult to get an overview of.

We have taken a closer look at some of the factors that can contribute to making interaction more difficult.

Variation in the organisation of municipal services

The municipalities have a duty to facilitate cooperation between services and several requirements have been set as to how this must be done within the health and social care services. Cooperation is, among other things, governed through agreements with the specialist health service and the use of individual plans. The duties stipulated in health legislation limit municipal self-governance.

This means that the municipalities can organise provision in accordance with needs within the framework set out by legislation. Municipal responsibility and interaction between the different agencies are arranged differently from municipality to municipality. The legislation accepts that there are variations in municipal health and social care services. The government’s escalation plan for mental health in children and adolescents for the 2019-2024 period also shows that there are variations in whether municipalities have proper services available for children and adolescents with mental health issues and disorders (3). The Children’s Ombudsman’s report “Jeg skulle hatt BUP i en koffert” (“If only I had CAP in my pocket”) also notes that the services available to children and adolescents in mental health are significantly under-resourced and that many municipalities are currently unable to provide proper mental healthcare to children and adolescents.

Instructions and guidelines designed to provide recommendations on how to design services for specific groups to ensure that these are in line with legislation have been prepared. The Norwegian Directorate of Health, for example, has issued national professional guidelines intended to help the municipalities identify vulnerable children and adolescents at an early stage (39). The guidelines state that the municipal management should ensure that the undertakings involved in the follow-up of children and adolescents cooperate with one another. The intent is for the parties to enter into cooperation agreements concerning customised local solutions. This results in loose national frameworks without any clear standards for how the service should be organised. The legal requirements set out for interaction and individual plans are not always implemented in the municipalities and there is not always sufficient capacity available in the health and social care services.

It represents a patient safety risk when the legislation allows for large variation in services and when the allocation of responsibilities is clarified through local agreements.

“In summary, there have been a great deal of meetings, but no measures aimed at our son’s learning situation.”

Jonas encountered a service in which several of the service providers were part of an intermunicipal cooperation comprising five municipalities. Intermunicipal cooperation has, in many contexts, been highlighted as a solution intended to ensure sufficient professional expertise in small and medium-sized municipalities. The Norwegian Local Government Act references different intermunicipal cooperation models (38).

The head of the intermunicipal cooperation: “We serve five municipalities which use different systems ... There are no doubts that this is challenging. At the same time, it would have been difficult for the municipalities to operate services such as the Child Welfare Service and the educational and psychological counselling service alone.”

The chief municipal medical officer felt that intermunicipal organisation could be cumbersome:

“We could probably have got where we needed to be at an earlier stage through simpler cooperation, I refer particularly to preventive work here. The way it has been, the responsibility and the services have been fragmented.”

The Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation has noted that it can be challenging for the municipalities to keep an overview of the overall task solution and execution of services in intermunicipal cooperations (40).

Fragmented responsibilities and complex services result in a risk of children and adolescents not receiving adequate, comprehensive or correct support.

Communication challenges between services

The duty to interact regarding patients is intended to result in reliable and necessary healthcare being provided. Good interaction within and between the services is a prerequisite for a common situational understanding and therefore also for a comprehensive service for patients and users.

Both refusals from CAP make reference to municipal services without CAP knowing what assessments and measures had already been attempted with Jonas. In the last referral, the GP had written that Jonas had been assessed by the educational and psychological counselling service. The consequence of the refusals from CAP was, in reality, that Jonas had no provision of support.

In 2019, the Norwegian Directorate of Health was commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care to carry out a knowledge-based needs survey. The report from the survey summarised the challenges children and adolescents with complex needs face during contact with the public services (41). The summary of the report notes that the system is fragmented and, to some extent, lacks cohesive understanding. Users are often referred from one service to another. It is the users themselves who end up having to take responsibility for coordinating the various services, which fail to communicate and cooperate. Despite this, users have little real influence.

Our investigation highlights the fact that inadequate cooperation procedures may constitute a risk to patient safety.

Lacking of information channels

In Jonas’ case, no systematic information channels had been established between the educational and psychological counselling service, school nurse, youth worker and GP. The services were organised in different ways and adhered to different legislation. The educational and psychological counselling service maintains that they achieved better results in the phases in which service providers worked in parallel, but service providers rarely worked in parallel and were also not coordinated. Follow-up was mostly sequential.

When service providers work independently with unclear responsibilities and a lack of clear objectives for the work, the overall situational understanding also becomes unclear. This represents a risk to patient safety.

The Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU) has prepared a report entitled “Fastlegens rolle i forebyggende og helsefremmende arbeid” (“The role of the general practitioner in preventive and promotional healthcare”) (42) on behalf of the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities. Due to the increased complexity and greater fragmentation of health services, the duties of the GP have become greater and more complex. It has become more challenging to coordinate and maintain continuity.

The fact that GPs are often not sufficiently integrated in or aware of the measures implemented by other municipal health services is also noted by the Office of the Auditor General of Norway (27). The Office of the Auditor General of Norway has investigated the authorities’ work to ensure good referral practices from GPs to the specialist health service during the 2014-2017 period. The Office of the Auditor General of Norway also notes that there is an unclear allocation of responsibilities between the primary and specialist health services.

There is a risk of children and adolescents not receiving a comprehensive service when the GP is not well integrated in municipal services, is unfamiliar with the services and is not a part of the established interaction procedures or information channels.

Reliable health services require relevant and necessary medical information to be available to the professionals that provide healthcare. Jonas encountered a system that lacked electronic interaction between services.

The duty of confidentiality and the understanding of this had been noted as a potential obstacle to interaction in the municipality where Jonas grew up. Incorrect understanding or too strict an interpretation of the duty of confidentiality may lead to necessary interaction not taking place and can be a challenge for comprehensive follow-up at a municipal level.

Interaction challenges between the municipalities and the specialist health service

The Office of the Auditor General of Norway has noted that unclear allocation of responsibilities between the primary and specialist health service means that patients who require mental healthcare do not receive a good enough service (27). A GP must always be familiar with the various CAPs, which have different procedures in place, as well as the allocation of responsibilities between municipalities and hospitals. They must also monitor whether there are any changes to procedures and allocation of responsibilities.

For the service providers, i.e. patients and the various service providers, it can be difficult to keep an overview of the organisation, allocation of responsibilities and how interaction must be coordinated.

Variation in service may, in itself, also represent a risk of failing interaction and therefore also a risk to patient safety.

Cooperation agreements and cooperation

The objective of the interaction reform (43) was to contribute to ensuring that patients receive the correct treatment in the correct location at the correct time. As part of the interaction reform, cooperation agreements were entered into between health trusts and municipalities to ensure that patients and users can access a more comprehensive service. How the agreements are designed and how well known they are within the system varies somewhat from municipality to municipality.

Cooperation agreements between health trusts and the municipalities are, in and of themselves, not sufficient tools to ensure the necessary interaction. Cooperation is strengthened when service providers meet. According to Erling Vik, successful interaction is dependent upon face-to-face relationships and teamwork (44). In a fragmented health service, service providers must be conscious of each other’s understanding, objectives and organisational conditions. This requires closer cooperation than is currently common and the service providers must cooperate more to follow up on those who require support.

The various forms of cooperation that have been attempted in connection with CAP referrals usually involve the various service providers meeting to cooperate on the assessment of the referrals. This strengthens a shared situational understanding. Successful interaction therefore requires the service providers to have good knowledge of one another and to be able to adjust to each other’s organisations and assumptions in general.

Need for closer cooperation

The government’s overall objective is for all children and adolescents to experience a positive and inclusive upbringing, play and learning environment and for more adolescents to complete upper secondary education. Public investigations, audits and research show that the various welfare services do not cooperate well enough to achieve these objectives in many cases. The government has identified a need for regulatory changes to ensure that children and adolescents receive a comprehensive service to a greater extent. In 2020, the government conducted a consultation on the regulations on cooperation between various welfare services and the coordination of services for children and adolescents (45). In the consultation paper, the government writes that “each municipality must be able to assess which roles the various welfare services will have in preventive and comprehensive services for children and adolescents, within the framework of the regulations”.

The government has also focused on the need for the municipalities and specialist health service to cooperate with regard to patient groups in other areas. In 2019, the government and the Norwegian Association of Local and Regional Authorities came to an agreement concerning 19 health communities (46). The objective of the health communities is to create more cohesive and sustainable health and social care services for patients who require services from both the specialist health service and the municipal health and social care services. One of the groups that will be given particular attention is children and adolescents. So far, few experiences have been obtained from the health communities and there is little knowledge of how these will work for adolescents who require mental healthcare.

The authorities are committed to achieving good interaction and the allocation of responsibilities and the form of work must be described through the use of cooperation agreements. Nevertheless, this does not result in clearer standards for the services and HIB believes that the parties must be compatible. It is difficult for service providers to stay abreast of the large number of agreements, the content of the agreements and where responsibility has been allocated.

The mutual duty of guidance

A key provision set down in the Norwegian Specialist Health Service Act is the specialist health service’s duty of guidance with regard to municipal health and social care services, cf. Section 6-3. Duty of guidance with regard to municipal health and social care services.

The provision is reflected in the Norwegian Healthcare Act (13)), which states that municipal personnel must provide the specialist health service with advice, guidance and information about any health-related matters necessary for the specialist health service to perform its duties pursuant to laws and regulations. These two laws stipulate that there must be interaction between service providers.

The specialist health service’s duty of guidance shall act as a safety net intended to help ensure the provision of the correct healthcare, including in cases in which the specialist health service finds that the patient is not entitled to prioritised healthcare from the specialist health service. The advice provided in the specialist health service’s response to Jonas’ GP was limited to referring to the municipality’s responsibility for further assessment and treatment. Other than this, there was no guidance provided in the response.

Could a patient pathway have helped?

The patient pathway for mental illness in children and adolescents was introduced after Jonas’ death. The patient pathway will start with the municipality, GP or another referrer, but is only registered and measured when the specialist health service receives a referral. So far there has been limited experience of the use of patient pathways for children and adolescents (47).

The patient pathways that have been introduced assume that the entitlement to necessary healthcare from CAP has been met. The patient pathway will be discontinued if the specialist health service finds that there is no entitlement to healthcare (22). Accordingly, the patient pathways do not constitute a guarantee that those who need healthcare will receive it. The introduction of patient pathways also does not change the threshold for prioritised healthcare for adolescents who experience difficulties.

Could an individual plan have helped?

Many people tried to establish what was bothering Jonas. You could ask whether Jonas should have had an individual plan.

Jonas did not have an individual plan. The health and social care services were not involved other than through the school nurse service. Much suggests that Jonas developed a need for coordinated services over time but his mental health issues were undiagnosed.

The supervisory authorities – from a user perspective

The supervisory authorities, consisting of the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision and the County Governor, are intended to, among other things, maintain an overview of whether the services fulfil their duties in respect of vulnerable groups. Supervision will contribute to ensuring that the population’s right to necessary services is maintained. The supervisory authorities are therefore part of the safety net around each user.

Appealing refusals

A patient may appeal a decision to refuse entitlement to healthcare to the undertaking concerned. In the event that the patient’s appeal is not upheld, the undertaking shall pass the appeal on to the County Governor for a final decision. The health service concerned must comply with the County Governor’s decision.

The County Governors continuously record appeals and supervisory matters in the NESTOR management system (48). NESTOR figures show that only 65 of the 7449 patients whose referrals for healthcare through CAP were refused complained to the County Governor in 2019. This means that less than 1 per cent of CAP refusals are assessed by the County Governor in the form of appeals. Around 40 per cent of these appeals were fully or partly upheld by the County Governor.

Liability in the event of serious adverse events – at the interfaces

The municipality did not have a duty to notify at the time of Jonas’ death, but the other legal requirements concerning healthcare were the same as now. CAP notified the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision of a serious event when Jonas died. The Norwegian Board of Health Supervision asked the County Governor to perform a follow-up audit. The County Governor performed an audit, but the audit was limited to only cover CAP’s assessment of the referrals from the GP.

When the County Governor performs an audit following a serious event or by request from the Norwegian Board of Health Supervision, such audits are performed to verify whether an undertaking or member of health personnel has fulfilled the legal requirements. Even though an audit was retrospectively performed, the normative function of the supervisory authority, with regard to both reliability and understanding of the duties within the service, will provide a key contribution to patient safety. The service must adhere to the assessments of the supervisory authority in its dealings with the next patient. This normative function constitutes an important outer layer of the safety net.

The County Governor’s assessment after Jonas's death

The County Governor concluded that there was no violation of health legislation. The assessment was limited to the role of the specialist health service and its assessment of the referrals against the requirements set down in the prioritisation regulations. Other legal requirements incumbent upon the specialist health service, such as the duty to interact and cooperate, were not assessed.

The County Governor’s assessment did not discuss whether Jonas, on the basis of the Norwegian Patient and User Rights Act (29) had already or should already have received the necessary healthcare from the municipality.

The County Governor concluded that Jonas was not entitled to healthcare from the specialist health service. In the assessment, the County Governor references the priority instructions for the mental healthcare system for children and adolescents, legislation and the fact that the issues related to school and academic function. The priority instructions state that school refusal alone does not entitle the patient to healthcare. They also state that other factors may change the eligibility status. It appears that one specific factor was emphasised by the County Governor and that other factors from the referrals were not given much emphasis in the assessment.

When the supervisory role is exercised to such a limited extent as here, it can contribute to maintaining unclear responsibilities and inadequate interaction in the service.

The responsibility for fulfilling the patient’s right to healthcare is split between the specialist health service and the primary health service. Since the supervisory audit performed after Jonas’ death was limited to assessing a very limited process in the specialist health service, the conclusion of the audit is of little value in assessing whether Jonas received reliable healthcare.

The approach taken by the County Governor after Jonas’ death did not fulfil the normative role that the supervisory authority should be expected to perform, i.e. ensuring that the overall service is reliable and upholding the rights of the patient.